This post originally appeared in New Geography on September 12, 2012.

In the last few decades, as suburbanization and deindustrialization devastated so many cities, they turned to two sectors that seemed not only immune to decline, but were actually growing: universities and hospitals. The so-called “eds and meds” sectors, often related through university affiliated hospitals, became a great stabilizer for many places. For example, the fabled Cleveland Clinic cushioned the blow of manufacturing decline in that city. Après steel, a city like Pittsburgh practically saw itself as defined by an eds and meds economy, with the new economic pillars being the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and Carnegie-Mellon University.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, these sectors have come to dominate so many cites’ economic development strategies. It’s harder to find a major city that isn’t touting some variation of a life sciences “cluster” as a strategic industry than one who is, and local medical schools and hospital complexes feature prominently in this. Similarly, technology transfer from schools is supposed to power startups, while in many cities growth in the number of students itself is supposed to be an engine of growth. For example, there are 65,000 students in the so-called “Loop U” collection of colleges in downtown Chicago, and education growth has been a bulwark of the Loop economy.

Yet in reality, overreliance on eds and meds is problematic. Firstly, these tend to be non-profit, and thus reduce the tax base in cities that are dependent on them. In danger of bankruptcy, Providence, Rhode Island was forced to ask for special contributions from Brown University and RISD, for example. Also, as quasi-public sector type entities, eds and meds are seldom a source to dynamism in communities in and of themselves. Indeed, universities are among the most conservative of institutions in many respects. Witness the firing and re-hiring of University of Virginia president Teresa Sullivan, for example, or faculty protests against the appointment of Indiana Governor Mitch Daniels as Purdue University’s next president due to his lack of an academic background.

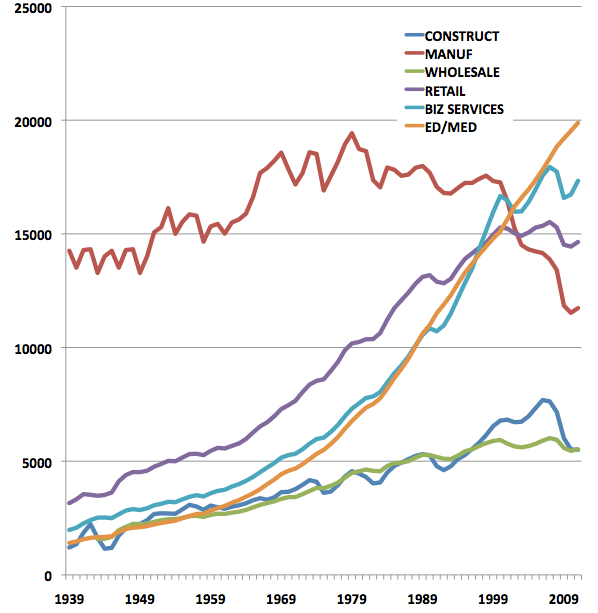

But for cities hanging their hat on eds and meds growth, a more fundamental problem now looms: these industries are at the end of their growth cycle. Spending on healthcare and college tuition costs has been skyrocketing at rates greater than inflation for years. Here’s a chart, via Atlantic Cities, showing job creation by sector since 1939:

If eds and meds employment has been going up continuously since 1939, what’s the problem? None, so long as it started from a low base at a time when other productive sectors of the economy were likewise growing strongly. But as sectors like manufacturing went into decline or stagnated, eds and meds has continued to increase relentlessly, accounting for an ever larger portion of total growth. For example, between 1990 and 2008, eds, meds, and government accounted for about 50% of all national job growth.

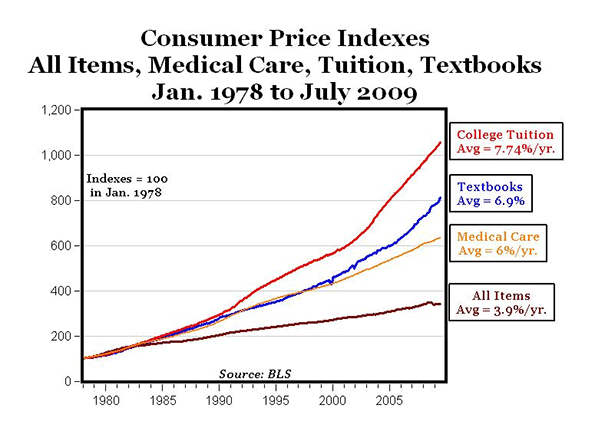

Unsurprisingly, with growth in jobs exploding, costs have followed. Medical costs and tuition have been growing at twice the rate of inflation, and at an increasingly divergent rate, as this chart from Carpe Diem shows:

Clearly, such a trend cannot go on indefinitely. As the US starts to groan under the weight of spending on health care and higher education, it’s clear that, as a society, we need to be spend less, not more on these items as a share of national output. Some cities with unique strengths, like Boston, with its many specialized biotech firms, or Houston, with the world’s largest medical center, may thrive in this environment, but the vast majority of cities are likely to be very disappointed in where eds and meds growth will take them.

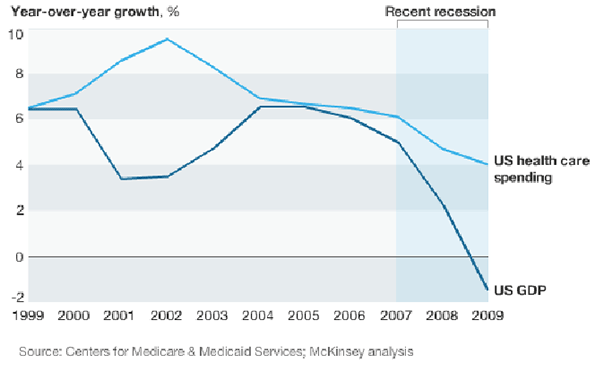

The problem with health care is most obvious. Aggregate spending on health care has been exceeding the inflation rate for many years. According to a report by McKinsey, spending on health care has consistently grown faster than GDP:

The net result is a sector that has been consuming an increasing portion of the national economy. Health care spending is projected to consume fully 20% of the entire US economy by 2021.

The health care reform act will do little to nothing to rein in this cost. It’s difficult to see how in fact the trend will slow. But with the federal government (especially through Medicare) accounting for more and more total health care coverage, $16 trillion in national debt, and large deficits and unfunded entitlements, one can safely assume that whatever can’t go on forever, won’t. Eventually the government will be forced to take action to stabilize health care spending.

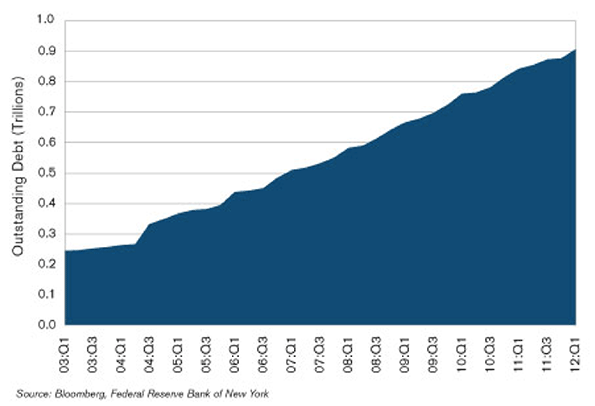

If the health care cost crisis has long been known, the public is just waking up to the crisis in higher education costs. Skyrocketing tuition has driven the cost of many colleges through the roof. This traditionally didn’t bother students, who were assured that a college education the key to a good job that would easily allow loans to be repaid. In a global age where even knowledge economy jobs are subject to offshore competition, and a recession that’s kept many young people — including many now deeply in debt — unemployed or underemployed. There is now about $1 trillion of it outstanding, much of it non-dischargeable in bankruptcy:

This student loan spike was created by many of the same dubious forces that led to the housing crisis. Indeed, some have said that student loans are the next subprime crisis, and commentators like Glenn Reynolds talk of a higher education “bubble”.

The overall economy will come back at some point, but it’s clear that America is reaching the point at which it can no longer pile more debt onto the backs of students. This by itself will serve to moderate tuition increases at most institutions. There is also a significant amount of reform the current system obviously needs that, if implemented, would also tend to moderate tuition increases. For example, it doesn’t seem unreasonable to suggest that colleges ought to have some skin in the game for these loans being repaid. Or that cheaper online education might substitute for physical classrooms in some cases.

Regardless of how it plays out, when you look at spending in aggregate in America, it’s clear increases in health care and higher education spending cannot keep increasing at current rates. This means that it just isn’t possible for all the cities out there dreaming of eds and meds glory to realize their dream. America simply can’t afford it.

Whether the end of the great growth phase in eds and meds comes 1, 5, or 10 years from now can’t be predicted. But come in the reasonably near future it will, and that’s when the bulk of the cities that put all their chips in those baskets will receive a very rude awakening.

“Houston, with the world’s largest medical center, may thrive in this environment,”

Wouldn’t this be a contradictory statement?

“This student loan spike was created by many of the same dubious forces that led to the housing crisis. Indeed, some have said that student loans are the next subprime crisis, and commentators like Glenn Reynolds talk of a higher education “bubble””

I wouldn’t rely on Instadunce and PJ Media to provide any level of financial insight…he and they are almost consistently wrong on just about everything.

“But come in the reasonably near future it will, and that’s when the bulk of the cities that put all their chips in those baskets will receive a very rude awakening.”

You mean like energy in Houston, the movie industry in Los Angeles, or the financials in NYC.

You might want to take a good hard look at what Barclays is already doing in London.

They will change, of course, but “end”? That is a much harder argument to make.

I find it curious that the two cities that I have lived in, both college towns, have had a hard time leveraging their innate assets to be an “eds and meds” center. These institutions, Yale in New Haven and Ohio State in Columbus, have added great stability to the mix, and their institutions in and of themselves are major employers. However, neither one has become a “break-out” city in terms of eds & meds.

New Haven has slowly added jobs in the area, and I read something recently that said it has a fairly high concentration of tech jobs per capita. Maybe that’s a “slow success”, but it still isn’t on the radar like Austin or Raleigh Durham, for instance. It hasn’t transformed the region’s economy.

Ohio State has fostered continued growth in Columbus, but not so much in tech. In fact, Columbus had a chance to be Austin in the early 2000’s, when CompuServe was based here and basically invented the early home-based internet service. Unfortunately they were bought out by AOL, and the principals, while they remain heavily involved in the local tech scene, haven’t seemed to create a tech explosion in terms of new, innovative companies that have put Columbus on the map.

On the other hand, one of Columbus’ great success stories is that its headquarters to several of the major fashion retailers that are ubiquitous in malls: the Limited and its acquired (and then spun-off) brands. How did Columbus become a major player in the fashion retailing industry? Was it all because Les Wexner lived here and founded the Limited, which changed fashion retailing in a fundamental way? Why didn’t CompuServe and OSU have the same results?

I’m rambling a bit, but I guess I’m wondering what that magic elixir is that makes some cities click, and others not so much in a certain industry. Seems to me that Columbus is a more likely Eds and Meds center than fashion, but that’s not how it played out. I’m sure many other cities have the same story.

The end of meds and eds is no where close to ending. In fact, on recent visits to both Cleveland and Pittsburgh I was absolutely amazed at these “fortress” industries. I would go so far to say that if each of these cities did not have their great universities and medical they would both be larger Hamilton, Ontario’s. Now I see Buffalo and even Raleigh/Durham are jumping on the bandwagon. I see no end to it and see this phenomena as a shining star in every city that has done it. Can anyone point to an example anywhere where this concept has not provided big dividends?

I often wondered about Columbus too, George. It never seems to fulfill its promise. Even Columbus’ overall job growth has not been spectacular in the last few years. Old school metros like Pittsburgh and Cincinnati have produced more jobs that Columbus, if the Bureau of Labor Statistics is to be believed. LIke you, I think it has something to do with where decisions are made. Columbus’ economy is dominated by branch-plant and back-off operations, with few headquarters for a metro its size. This means it hasn’t become an informational ‘node’ where the future of given industries or businesses are developed. That seems to happen elsewhere and only then carried out in Columbus.

Clearly “eds and meds” are facing big systemic change.

“Fortress industries” are very vulnerable to big systemic change. (See: Detroit autos, Pittsburgh steel)

Just look at the demographics alone. Boomers will increasingly age out of “peak healthcare” (die) over the next 10-20 years (our generation is now 49-67), and GenX is much smaller in number.

The current demographic bulge of GenY/Millenials (now 13-31) will age out of university education over the next 10-20 years also.

There is also actual reform pressure on healthcare delivery costs, and some pressure on university student loans as well as cost pressure from MOOCs. So in addition to shrinking potential US markets, both industries face cost/financing pressures.

Chris makes valid points. However, I still contend this eds and meds play could run for another 20 years or longer. Spending on healthcare seems inelastic. Education not so much.

I think Aaron was referring to the end of the boom for “eds and meds”, not an imminent collapse of the industry. We clearly can’t afford to keep paying the skyrocketing costs, especially as our unemployment and work participation rate remain so low, with the wages of those who are employed continually decreasing, or at least not keeping up with inflation.

What will happen when the Obamacare requirement to buy insurance is implemented, but without anything to bring down costs? When the IRS must fine tens of millions of Americans for not buying the health insurance that they can’t afford, perhaps the government will be forced to impose health care cost controls. At that point, a decline or reversal of the growth of the “meds” industry will be inevitable.

Paul, this may be true of community hospitals and small centers but the large academic and research funded big city hospitals will still be there and most likely pick up the slack of these. The country has a vested interest in this. The strong institutions are in a great position no matter what in my opinion.

Matt:

I kind of agree-I think Columbus could be an Austin, and in that way it has underperformed. However, I think overall Columbus has been doing well, just not in the areas you would think. From what I have read (haven’t looked at BLS) it’s been in the top 20 large metros for job growth the past few years. Do you have a good data source that’s easy to access? I would be interested to look at it.

As for the headquarters issue, according to the Columbus Partnership, we have the highest concentration of Fortune 1000 HQs per capita of any metro in the nation. We do also get a lot of back-office jobs, but I would disagree with the assertion that our growth is all due to back-office work.

Ironically, it may be that we are too diversified to really hit the accelerator and get to that Austin level of job growth.

I don’t know that I buy the end of Eds and Meds, either. The share of spending on various categories by households is shifting. If globalization is greatly lowering the cost of goods, we’re likely able to spend more on services. See attached bar chart:

http://blogs-images.forbes.com/chrisconover/files/2012/12/healthprices.jpg

The BLS metro employment numbers by metro area are here: http://www.bls.gov/eag/. Columbus has done no better than Cincinnati or Pittsburgh in the last year, for example. This contradicts the popular narrative of Columbus as vibrant, young, midwestern boomtown and Cincy and Pittsburgh as stagnant old rustbuckets struggling to find their way to growth again. I think the problem is more Columbus though. It should be doing much better than it is. Does the relative absence or presence of eds and meds help to explain these metros?

I think it has to do with networks of knowledge and experience in each metro. There is much value in the webs of economic relationships and supply chains of older metros, even if they come with the greater costs of brownfields, aging infrastructure, and more complicated local politics. I lived in Columbus for four years and the lasting impression I was left with was of a transient place where people didn’t know each other and often had no interest in doing so since they expected to move on for their next job. Columbus was a job for many, not a place to live. Many treated it as a kind of ‘campus’ where they sought to develop themselves for their real life somewhere else, not a home in which they sought to invest their social capital. Though that is probably how many would describe Austin or Raleigh too, it is most certainly not the case for Cincy or Pittsburgh.

The more I think about it, eds are dead or going to be, meds no way for the foreseeable future. But just like, big city hospitals in Cleveland or Pittsburgh, the urban eds, i.e. Case in Cleveland and Carnegie in Pittsburgh will thrive because they have ability to do so. The industrial education complex will wither away in so so locations and so so quality that grew during the boom years (see all the various state and low end private colleges).

Michael, I think even high-end colleges and universities will face challenges. Their “fortress” is their huge capital investment in facilities and research, bolstered by alumni connections and contributions over time. But if everyone can take courses from Nobel laureates untethered from a campus…

MOOCs will deliver learning at almost no capital cost. After all, lectures and exams are just…software.

Kurt Vonnegut’s “Player Piano” was amazingly prescient, but he stopped at factory automation. He never envisioned great courses taught by the greatest academic experts…available to all. Or, in software terms, massively scalable at almost no marginal cost.

What does a professor’s $300,000 salary cost per student when there are 300,000 students? How much time does he save for research by only having to prepare and record lectures once per course? (Research assistants, grad students and adjuncts already work for almost nothing grading papers.)

Maybe not today, maybe not tomorrow. But soon, and for the rest of your life…

Chris, my students at a large regional university want MORE professor contact, not less. They want the chance to do original work and to present it. They say they want to have choices and to do internships and work/study. This is all the opposite of MOOCs. If everyone can do something, how valuable is it? Instead of automating the old model of education, a new more interactive model of education is replacing it. How can an online course lead to meaningful references from faculty, job placement, opportunities for students to present original work, or contact with fellow students, all of which are important ways to locate professional opportunities? MOOCs are another example of the utopian fantasies of techies, not real solutions to a sputtering market in education, training, and an improved job market.

Meds spending is inelastic? Which is why Medicaid and Medicare reimbursement rates are collapsing? People are also putting off out of pocket medical spending.

“my students at a large regional university want MORE professor contact, not less.”

Students may also want fancy campuses and sports facilities- the question is how many will be willing and or able to pay for it. The vast number of courses taught by adjunct faculty at most research universities shows how weak the model is. Isn’t a MOOC course actually taught by a top professor of greater value than many courses taught by adjuncts and grad students?

My spin on this is different. Dense cities like NY, Chicago and Pittsburgh may benefit from trends towards cost cutting and continuing education. The CUNY, SVA, Parsons, FIT, Point Park model, is in theory much lower cost. No surprise many for profit operators locate in central cities.

Tech Shop and Hacker spaces are good examples of the trend towards informal learning well suited to cities.

My students don’t seem to care about fancy facilities like they did a decade ago when I started here. Maybe that is why my institution is now offering health club memberships to anyone in the area. The rec center looks empty when I walk by it on many evenings. Many of my students can’t use it because they work so much to pay their tuition.

No professor can be all things to all students. Most of my students would have a hard time relating to the lectures of an ivy-league academic. My contextualization and written and oral responses to them are often the only substantive academic feedback they’ve received in years. Universities, colleges, departments, and students are all changing at the same time. To imagine that the mode of instruction will change while everything else about universities will remain the same is too simplistic.

I’m closer to agreeing with you. MOOC’s alone are not likely to take over the world. Much more likely is new models that share the best of both worlds.

Smart colleges will dump the capital cost of amenities like cafeterias, sports and entertainment facilities by locating where they already exist.

An à la carte model where people get degrees by taking a range of different courses at best of breed schools may develop.

It’s interesting that the Las Vegas, downtown project sees education as a big component, but has chosen not to involve any formal university. Instead, there are plans for conference spaces and a Tech Shop, where people can learn to use high tech equipment and work on collaborative projects.

No surprise that a major hub for Bushwick’s art scene is a collaborative learning/ work space called 3rd Ward.

https://www.3rdward.com/

Pittsburgh has a number of great informal learning options, like Pittsburgh Filmmakers, Artists Image Resource, The Pittsburgh Center For The Arts, Hack Pittsburgh, Silver Eye and now Tech Shop.

John, Matthew: I am not suggesting that things will remain otherwise the same! Big changes in structure and delivery will come.

As with many other things in US life, higher education offerings will gravitate toward the poles. The “working person” colleges will likely be the low-cost community colleges, probably heavily supplemented by distance-learning and MOOC technology.

The Ivies and other elite national universities will probably thrive as content providers. The general state-branded (but increasingly less state-supported) football and basketball factories with middlin’ academic records are probably facing some trouble.

President Mitch Daniels at Purdue bears watching, because in all things he watches the numbers. He started with tuition and staff freezes…even at one of the US’ top 10 engineering/tech education centers.

What I’m saying is that part of the structural problem for a lot of schools is location.

But doesn’t Purdue have a basic structural problem in terms of its location? I mean, a big campus & the need to provide all kinds of amenities to make life interesting enough to go there? Can they do a business in continuing education as easily? (don’t know much about Purdue)

You can have a 3rd tier school in NYC, Philly or Chicago and some kids will want to go there or attend cause they live there. Ditto, with faculty. If the school “folds” perhaps another one will pop up nearby.

Chris, I think your view of learning is just too simplistic. Learning is not the insertion of standardized ‘data’ into human brains. People aren’t machines. Each person actively forms their own ‘knowledge’ from what is available to them. A world in which people will ask, “what biology did you do, Harvard, Yale, or Stanford?” will never exist. A world in which people ask, “what original work have you created or presented?” will.

Some Hospital/ Healthcare Layoffs announced in the last 10 days or so.

Bay State Medical Center in Massachusetts, 29

Duke Raleigh Hospital in North Carolina, 27

Western Connecticut Health Network 116

Harvard Medical School, 31

Lourdes Hospital, Paducah, Kentucky 29

North County Hospital, Vermont 19

Baptist Health System, San Antonio Texas, 40

Vanderbilt University Medical Center, Nashville Tennessee “some layoffs”

Grinnell Regional Medical Center, Iowa, Eliminates 41 positions- 23 through layoffs.

http://www.dailyjobcuts.com/

Oh, lets add

St Vincent Health, in Indiana which is cutting 865 jobs at hospitals across the state.

And..

Maine Medical Center offers 400 buyouts.

Parma & Medical Device companies have also been heavy job cutters in the last few years.

I wonder who is going to deliver healthcare to all the newly insured people.

From Slate today:

http://www.slate.com/articles/technology/technology/2013/07/georgia_tech_s_computer_science_mooc_the_super_cheap_master_s_degree_that.single.html#pagebreak_anchor_2

—

Matthew, I wouldn’t characterize my views as simply as you have. (#23)

However, more than one friend with an advanced degree in the sciences has described the “scratch and sniff” that such folks do upon meeting, to ascertain their rank in the academic pecking order.

In other words…people DO compare whether they “did” Purdue or Vanderbilt pharmacology, Duke or Stanford biochemistry, etc.

This is especially true after the actual academic work (in any field) is long-obsolete: the reputation of the school in your field carries weight.

Sure, this is distinct from selling skills and proving deliverables in a job-interview setting…but today, automated resume screening is what gets you in front of someone to describe what you’ve delivered and what your promise is. Doesn’t it seem likely that “Harvard”, “Yale”, “Penn”, “Stanford” and “Columbia” get pings when a search is screening people with MBAs?

I don’t think it’s really any different in the academic world, either. Top schools hire faculty with degrees from top schools.